Has your union representative made a difference for you and your colleagues? Then you can say thank you by nominating them for the Union Representative of the Year award.

News

"Once you start cleaning floors as a PhD, you lose faith in yourself”

Mozhgan Gerayeli got rejected from jobs because of her name. Today, she helps high educated foreigners and Danes finding a job in their fields.

Mozhgan Gerayeli receives Agnes and Betzy award of Thomas Damkjær, IDA’s chairman, in 2019

When Mozhgan Gerayeli graduated as a software engineer in 1996, the world was at her feet.

She was one of only two women who had graduated and the only female with a foreign background.

Her aunt had come from Canada to attend the graduation ceremony at the University of Southern Denmark, and the proud family member insisted that she and Mozhgan took a picture with Anker Boye, Mayor of Odense.

Mozhgan had been very conscious about choosing a field with a low unemployment rate, and even before the ceremony, most of her fellow students had already landed a job. Therefore, she took it easy and waited to send out applications.

But when she started looking for work, things did not go as expected.

"I sent over 100 applications without a single interview, and I could see that they did not read them at all because several of them wrote Mr. Mozhgan Gerayeli in return, even though I wrote that I am a woman. So, I believe I only got rejected because of my name”.

Her suspicions were further supported when she realised that most of her fellow students with a non-western background who struggled to find work in their fields.

"My ex-husband was also a software engineer, but he lost his hope and opened a pizzeria instead. I also knew others who were electrical power engineers who gave up and took unskilled jobs".

The experience was not unique to Mozhgan and her fellow students. A study from Aarhus University has shown that graduates with a Middle Eastern name generally submit 53 per cent more applications before they get a job interview.

Today it is the purpose of Mozgan's work to help high educated foreigners and Danes with foreign background find a job, for which she was awarded, among other things, with the Agnes & Betzy Prize in 2019.

But the road to get there was not easy to navigate.

A strong desire to perform

For Mozhgan, the turning point came during a trip to Copenhagen when she was recently graduated and still unemployed, and she passed by the office of Ericsson, the telephone company, in Sydhavn.

"When I saw those beautiful buildings of glass, I felt a deep desire to work there. I even looked up and imagined a particular office that I would sit in and work at some point."

"For the next three months, I wrote 40 applications to Ericsson, and I kept calling them. In the end, I think they got so tired of me that they just offered me an interview. It was my first interview, and as I sat on the train on my way home, I could not wait to phone them and ask if I had got the job. Later, my boss said they hired me because I was so passionate."

Once Mozhgan got access to the labour market, her career got wings.

"It was as if my name was not important when I first had Ericsson on my CV. It was a seal of approval."

In 2004, she got her first job as lead manager, and she felt that her career was on track. But she also worked very hard and was always striving to be the best.

"I worked 80 hours a week and put a lot of pressure on myself to be the best all the time. When I finished work, I trained Crossfit and boxing, male-related sports to show that I could handle anything."

The strong need to perform goes back to Mozhgan's upbringing in Iran, where she lived until she came to Denmark at the age of 21 when her ex-husband fled the clergy and the Iran-Iraq war.

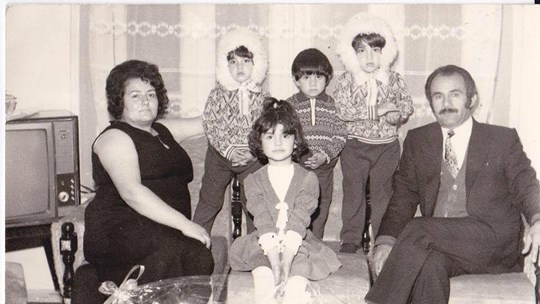

Mozhgan and her family in Iran

Although she came from an academic family and had the support of her parents to study. Iran was turning into a conservative, male-dominated society after the Islamic revolution, and Mozhgan had a long way to go in her adult life to prove that she could achieve as much or more than men.

But at one point, Mozhgan had pushed herself so hard that her body could not resist anymore. In 2012, she travelled to Greenland, where she intended to assist in the merging of two IT companies.

"It was a quiet place where people went fishing, the sun was shining and not in a rush as much as in Copenhagen."

The calm surroundings meant that she suddenly felt her inner turmoil, and after a short time in Greenland, she signed off work with stress.

Mozhgan's arrival in Denmark in 1986

Karin got the job. Mozhgan did not

After a few months in Greenland, Mozhgan returned to Denmark to a different life.

"I rented out my apartment, I sold my car, and did not received a high salary anymore, I had reached the lowest point. I completely lost confidence and countless applications without getting a job reinforced this feeling".

"At one point, I did an experiment where I sent two applications to the same company. In one, I used my name, and in the other, I wrote Karin Jensen. When Karin got a job interview, and I did not, I got angry. My name was a problem again".

Mozhgan ended up changing her career path. She took a stress management training program and dedicated her time to graduates who had been on sick leave.

However, this turning point offered a new opportunity to work with high educated foreigners and Danes from different ethnic backgrounds.

"At one point, an Iranian couple contacted me. Both had a PhD degree and needed help to get access to the Danish labour market. I was not a career counsellor, but I invited them anyway, and it turned out that I could help them find a job."

A workshop in cultural understanding organised by Mozhgan's company

"The experience was a wake-up call. In front of me was this social issue that I could help to solve. We have in this country several thousand international and Danish graduates with different ethnic backgrounds unable to find a job".

You lose confidence when you start cleaning floors as a Ph.D.

Mozhgan started Mozhi Consulting to focus on her new passion, and she has gradually expanded her network by using social media. Today, she has helped over 135 people to find a job.

It is often about rebuilding applicants' self-confidence and telling their story in a way that appeals to employers.

"If you ended up cleaning floors with a PhD, you would lose something of yourself. I help them focus on their strengths."

"Also, we look at their applications and CV. Many people have a gap in their CV because they took unskilled jobs, such as packers at nemlig.com or similar.

We place this information at the end of the CV, and we write that they took the job to integrate, be an active part of Danish society or to improve Danish. Instead, we focus on their strengths and how they will help the company solve a problem."

"This approach is about storytelling. It is a question of showing companies that they are not lazy or parasites, as some may think."

Mozhgan also makes sure to make initial contact with a possible employer on behalf of the candidate, either unsolicited or a job posting.

"They always ask why it is me and not the candidate himself who is calling. Then I say that as foreigners, they may experience some prejudice. Later I explain a little about their background and that they have been in an integration process with me, where they have learned about the unspoken rules shaping a Danish workplace, which can often be difficult for foreigners. The result is that companies usually show interest in the candidate".

In this way, Mozhgan helps applicants get a foot in the door, but then it is up to the candidates themselves to secure the job.

"Once, I called on behalf of an applicant from India, and the manager immediately said he was not interested because Indians were not proactive on the job, they only do what they are being told."

"I persuaded him to take a five-minute meeting with the applicant, and when we sat in the room, he immediately started asking how they were doing at work. After 30 minutes, the manager said I could leave them alone, and they ended up talking to him for 2 hours and hiring him the next day. He has been in the company for three years now, he has been an employee of the year, and he has gone from a monthly salary of DKK 30,000 to DKK 60,000" Mozhgan says.

Danish norms are a challenge

One of those Mozhgan helped was Shilan Ahmadi, who is a graduated industrial engineer and now works as an APQP process lead at LM Wind Power, which produces wind turbine blades.

She had long dreamed of working abroad and decided to move to Denmark in December 2014, after she had been working on a project with a wind farm in Iran where Vestas was involved.

However, in the beginning, it was difficult for her. She delivered newspapers and worked at a Mexican restaurant, but although she was happy to have a job and felt part of society, the situation was stressful.

She left a good job and her family in Iran, and now she was struggling to find a job in her field.

Mozhgan and Shilan Ahamadi

She says that Mozhgan helped her find peace and confidence, but also to understand the unspoken cultural codes in Denmark.

"In Iran, the labour market is very hierarchical, while in Denmark it is flat. I did not understand that at first, which is why I was formal and overly rigid in job interviews when the manager was present. But what I did not understand, was that I made the situation uncomfortable for them and therefore they could not imagine having me as a colleague. "

After practising what to do in a job interview in a Danish context with Mozhgan, the situation changed significantly for Shilan, and in June 2016 she had three job offers after a year and a half in Denmark.

She eventually chose Siemens, where she worked for two years, and later worked for GE Energy and now for LM Wind Power.

Mozhgan and Zara Hassanzadeh Hosseini, she has an MBA in Marketing

Another person that Mozhgan helped was Zara Hassanzadeh Hosseini, who has an MBA in marketing and came to Denmark from Iran in 2015 with a Green Card.

"In Iran, I worked for a company that distributed to five Danish companies, and I had been here on business trips. So, I had a network and expected it to be easy to get a job in Denmark, but it turned out to be a difficult process".

The first and a half year Zara lived in Denmark, she took several jobs outside her field: in a warehouse, as a fitness instructor and as a bartender. During that period, she kept getting closer every time she applied for a position in her field.

She got job interviews and was told that she was a fit for the job but got always declined at the last minute. It eventually undermined Zara's confidence and belief that she would find a job, and that hope was what Mozhgan helped her to regain.

"She helped me with my confidence and remembering what I had done in the past. But the good thing about Mozhgan is that she adapts her help to the individual. I have sat in her office where she helped people who struggled with Danish culture or with completely different challenges. She sees the individual and makes you feel like you are not alone."