Salary and negotiations

Go to salary

Salary can mean many things - get an overview of how you can benefit from IDA's salary tools.

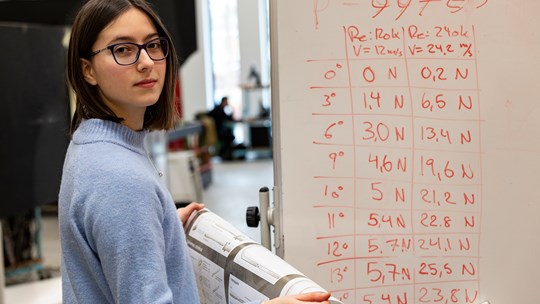

Juliana Glahn is one of the only women on the mechanical engineering programme. The Danish education system is highly gender-segregated, and this affects equality throughout the labour market.

When 21-year-old Juliana Glahn sees the students studying design and innovation at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU), she thinks that she would fit in perfectly, at least on paper.

"There are a lot of young women there who, like me, like to draw."

However, on her own programme in mechanical engineering, where she is on her third semester, she stands out. When she started on the programme, there were only three girls in her class. Today, she is the only one left.

The mechanical engineering programme attracts many students with a practical background, and the humour can get a little crass, especially in workshop subjects, says Juliana Glahn, but stresses that she is thriving and likes the company of her fellow students.

This is one of Denmark's most gender-segregated degrees, and at study start last summer, only five per cent of students were women. But this is far from unique in Denmark, where men and women concentrate on different programmes.

Men are predominant in most financial and technical programmes, while more women study the humanities or health and social care subjects.

This has an impact on gender equality on the Danish labour market.

The CEPOS think tank has ranked the programmes that give the highest salaries, and here men are predominant on 16 of the 20 higher education programmes that lead to the best paid jobs. On the other hand, there are most women on 13 of the 20 programmes that result in the lowest salaries.

Choice of education is also the factor with the greatest impact on who become leaders. An analysis from Boston Consulting Group shows that engineering degrees and degrees in economics and business economics in particular pave the way for a career in management, and here, women only constitute around 30% of students.

This trend not only applies to higher education programmes. Denmark is the fifth worst country in the OECD for gender equality on vocational training programmes. For example, 98% of students on the programme for dental assistants are women, whereas 98% of future electricians will be men.

Juliana Glahn herself has never experienced anything but a positive response when she tells people that she is studying mechanical engineering.

"My parents' generation in particular thinks it is great, and they help me a lot."

There are no barriers that discriminate on the grounds of gender in the Danish education system. Denmark is a top scorer in the World Economic Forum's annual Gender Gap report measured on equal access to education. Like the Swedes, Norwegians, Finns and Icelanders, Danes are among the nationalities with the most positive attitude towards gender equality.

Therefore, some researchers talk about a gender-equality paradox: A study conducted by psychologists Gijsbert Stoet from Leeds Becket University and David Leary from the University of Missouri has shown that there are fewer women in STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) in countries with a high degree of equality.

This means that countries like Algeria, Tunisia and Turkey educate more female engineers than the Scandinavian countries.

According to the authors behind the study, there may be several explanations for this.

One is that women who are discriminated against in society will be more motivated to pursue an education that guarantees them prestige and a sense of security. This is not necessary in Denmark, where woman do not experience direct discrimination because of their gender.

This explanation suggests that women are generally more interested in the humanities and health care and social care, and that this is what they choose when they have the freedom to do so.

According to the researchers, another possible explanation is that both men and women choose education based on their relative strengths.

PISA surveys show that boys perform best in mathematics in most countries. Girls do just as well or better than boys, but they are even better at reading, and therefore they are relatively stronger in non-science subjects. This difference may therefore be an indication that girls choose a direction, in which they feel that they have the greatest potential to exploit their skills.

Christian Gerlach,

Professor at the Department of Psychology, University of Southern Denmark

Studies like this show a correlation, but they cannot identify the reason why men and women apply for different programmes.

The explanation according to some researchers is that, from a young age, girls and boys become socialised into pursuing different directions. Others believe that it is a result of the different biologizes of men and women.

In 2017, software engineer James Damore was fired from Google when he criticised the company's policy on diversity in a written document.

In the document, he argued that men more often become leaders and programmers, because they are naturally more interested in systems than women, who are interested in social relations and human beings.

Damore was supported by Lone Frank, a science journalist on the Danish newspaper Weekendavisen, who wrote that there are ‘well-documented findings’ that prove that men and women are biologically different and that this affects their preferences.

Christian Gerlach, a professor in cognitive neuroscience at the Department of Psychology, University of Southern Denmark, is sceptical of this view.

He suggests that gender roles vary across time and cultures, and that environment is therefore more important than biology.

"When you take a closer look at the studies referring to fixed personality traits, for example whether you are helpful towards other people, not only the gender, but also the culture in which you were raised, has influence.

Generally, it is almost impossible to find a single cognitive or personality skill that only men have or only women have. The differences we can see are very small, and they are far from large enough to explain the differences in the education system," he says.

In primary and lower secondary school and in upper secondary school, Juliana Glahn felt neither particularly good at, nor confident in, mathematics and physics. Therefore, she long considered whether she would be able to keep up academically at the Technical University of Denmark.

Ultimately, the decisive factor was her life-long dream of becoming an inventor and creating something herself: She wants to build a machine that supplies her home with electricity from ocean wave energy, and she wants to invent and install an irrigation system in her garden.

"If that is what I want, I have to understand fluid dynamics and the properties of different materials. Mechanical engineering gives me the best outset to be able to design a product and calculate what it can tolerate.

I realised that I had to pursue this direction when I was at upper secondary school. At that time, my plan was to become a designer, and I had made this lamp with a wooden base that I thought was beautiful and aesthetic. But I realised that I had to make sure that it did not burst into flames when the hot light bulb touched the wood. I decided there and then that I wanted to be good at maths and physics, so I no longer had to depend on others."

Many girls lose confidence in their mathematical and scientific abilities during school, explains Henriette Tolstrup Holmegaard, an associated professor at the Department of Science Education at the University of Copenhagen and a researcher in choice of study programme.

Furthermore, there is a discourse that you must be particularly intelligent to study a STEM study programme.

"Studies show that girls underestimate how good they are at mathematics and science, and this can become toxic if they also think that they have to be more than ordinarily talented to study these subjects.

Because in fact girls are no less interested in mathematics and natural science than boys," explains Henriette Tolstrup Holmegaard and refers to a research project from University College London:

"If you ask girls in primary and lower secondary school and in upper secondary school, they say that STEM programmes are exciting, important for the future, and that the world needs people working within these fields. However, they also say that this does not include them."

Henriette Tolstrup Holmegaard's own research shows that identity is an important factor in young people’s choice of study programme.

When Juliana Glahn read about mechanical engineering on the Technical University of Denmark website, she noticed that she was not a typical student for this programme.

"There was a video with a lot of older men and only one woman. But I tried to focus on the programme description, which said that I could design and produce solutions for the future, and this was important to me. But I think that many people look at the visual material, and if you are a young girl just out of upper secondary school, where you've had fun with your girlfriends, this may seem a little discouraging."

The problem is not only expectations for the programme, but also the everyday student life that many women experience on STEM programmes.

Several studies indicate that social framework and study culture affect whether students feel they belong on a programme, and here gender is very important, explains Henriette Tolstrup Holmegaard.

"We should not try to fix girls, but rather we should look at what we are actually offering them. We should try to do something about the study environments to make them appeal to different types."

Her research shows that study environments differ across programmes with an imbalance in the distribution of gender.

Men who are in the minority on molecular biomedicine programmes have other challenges than women who are in the minority on computer science programmes. However, there are also differences in what it is like to be one of the minority of women on computer science compared with being one of the minority of women on an engineering programme.

Nevertheless, there are some general challenges for all the programmes on which women are in the minority:

Teaching may be organised such that focus is on finding solutions through play and experiments. Several studies show that this makes it more difficult for women to engage in specific studies, because their most important motivation for applying for these programmes is a theoretical interest in the subject.

"For example, on computer science programmes there is an ideal that you nerd around with a problem for days, and if you ask for help, you will be looked down on. This can be challenging for women, who prefer working together."

On many studies, it is up to students themselves to organise social activities, and according to Henriette Tolstrup Holmegaard, these activities often involve getting drunk together if the majority of students are male.

"It is not because women do not enjoy a Friday afternoon beer, but I've spoken to several students in my research, who feel encroached upon by flirting at these events, because there are almost no women.

“Educational institutions should therefore support several different social activities if they want to attract and retain different types of students. Because the social framework is very important for student satisfaction and therefore also for the number of dropouts from programmes."

Juliana Glahn has not had any unpleasant experiences of this type on her programme. Instead she considers her time on the programme as preparation for working with her future colleagues when she has finished studying.

"It will be like on the programme. l probably would not be able to mirror myself in many other women, but that is okay, ultimately it is about doing a good job - regardless of gender."