Has your union representative made a difference for you and your colleagues? Then you can say thank you by nominating them for the Union Representative of the Year award.

News

Imagining the ideal working life of the future

Techfestival participants called for a meaningful working life full of community, connection, and creativity at IDA’s workshop.

Techfestival is a yearly festival created to find human answers to the questions that tech progress gives rise to. Aspiring to be the leading voice of technology, IDA has been a partner for the last two years, in order to support and participate in the important conversations about technology, society and ethics.

The tiled room in the Meatpacking district, where IDA held its session on the future of work were packed to the max on Friday afternoon during Techfestival. As the waiting line queue emptied out, the room held 90 people ready to get inspired from the three speakers IDA had invited to inspire and frame the workshop. Participants were a very broad mix of both internationals, Danish nationals, employers, employees, freelancers, start-ups, students and researchers.

Future Systemic Transitions Need Humans, not Robots

The first speaker to set the stage was Indy Johar (UK), architect, entrepreneur and high in-demand speaker on systemic change. Johar has co-founded Dark Matter, a field laboratory focused on radically redesigning the infrastructure of our cities, region and towns. On this occasion, he gave a sharp analysis of the structural transition that will define the future of work. First, he argued, there will be no shortage of work. The global challenges that we face will require huge amount of work from humans. Work of the future will unlock and demand our creative and emotional potential, and not, like the automation narrative would have it, consist of robotic tasks. Second, Johar said, we need to redesign our institutional models in favour of public, not private ownership. Our shared commons (e.g. culture, data, environmental assets and public liabilities) are the primary source of value creation, and by implementing a many-to-many platform model, they can work as utilities for the public instead of private ownership. In short, goodbye robots and automated labour, hello creative, emotional and real human labour and distributed value-creation.

Creative and Critical Humans for the Future

The next speaker, internationally acclaimed writer on digital culture, the digital revolution and its blind spots, Katrine K Pedersen (DK) kept a ‘humans are not robots’ approach and emphasized the importance of nurturing culture, art and play, in a future tech-driven society. Pedersen, Head of Communication and Education at ARKEN Museum of Modern Art, reminded us that not everything can be instrumentalised, datafied and automated, nor should it. Pedersen reminded participants of Silicon Valley, which was once a melting pot for art, philosophy, new ideas and movements, but which turned into a “cold epicenter of venture- and surveillance capitalism facing huge ethical problems”. Not an ideal role model for the future. Instead, Pedersen argued, ‘unproductive’ activities such as play and dreaming are highly important activities that we need to nurture in order for us to stay creative and critical: “What the arts allow us to do is develop the muscle required for discernment, and also strengthen our sense of agency to determine for ourselves how we’re going to tackle a given problem”.

Purpose and Connection over Commercialization

The last speaker, Ryan Chatterton (US), founder of Coworking Insights and expert on coworking, new work and mobile productivity, brought us back from the future to today, and shared his experiences and reflections on freelancing, digital nomadism and the rise of co-working spaces. According to Chatterton one of the biggest downsides to freelancing is the lack of community and connection. You might be free, but with this freedom comes loneliness and isolation. Co-working spaces then, has been a way for remote, independent workers to re-establish the sense of connection. After the co-working space as a concept has been commercialized by huge corporations (such as WeWork) it seems as if it has lost its purpose and has turned into a real estate strategy, said Chatterton. As such, the digital nomads are back to scratch and in dire need of ways to re-establish connections with others and to share a meaningful purpose. This is why Chatterton believes that in the future, people will get back together (physically) and realize that ‘there is something lost when your only connection is through a fibre optic line’.

Tendencies in the Labour Markets of the Future

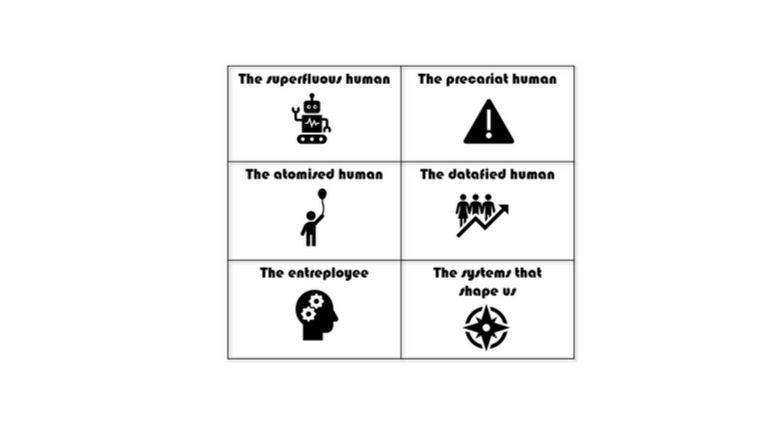

Today’s labour market is characterized by a lot of changes in the way work is structured. We are moving from traditional factory jobs to self-management, from gold watches at 50th anniversaries towards a gig economy, from clocking in, to working in cafes at all hours, from tangible products to complex services, from collegial communities at workplaces to individual careers, and from human relations to digital assistants predicting our wellbeing. Extrapolating these tendencies, we came up with six condensations to frame the workshop.

The superfluous human alludes to the increased automation of work and the (crucial) role of humans in a labour market where robots begin to outperform what we do. The entreployee (not to be confused with the intraployee) is a hybrid between the employee and the entrepreneur born out of the need for workers to behave like entrepreneurs, even if they do not own a company. A major trait of today’s labour market is the need to relearn skills throughout one’s life and operate in a world in which it is crucial to constantly reinvent oneself, adapt, be innovate and "disrupt" oneself, or you lose. This puts a permanently urgent demand on the entreployee to optimize their time, their mind, their body, their trade in order to stay relevant.

The precariat human describes the class of people whose lives are uncertain and lack security, because they work on short term contracts or irregular hours, resulting in a loss of standard labour protections and benefits associated with the traditional employment contract. This kind of work also shapes the atomised human who embodies the atomization of work as the spread of freelance- and remote work as well as the gig economy leads to more and more people working alone.

The datafied human refers to the general development that on one hand is driven by digitalization, and the other hand a demand for efficiency and evaluation. People are reduced to data and algorithms, trying to track workers performance and wellbeing at their workplace, in order to increase productivity and avoid loss of talent. The last category covers all the systems and structures that enable, shape, sustain and lock all these tendencies in, including the impact of climate change and globalization on our working life, the economic tides, to geographical and gender-based inequality.

Techfestival 2019

What the Ideal Working Life Looks Like: Focus, Meaning and Connection

Working on each of the six tendencies, the participants called for a working life characterized by more focus, meaning and connection. There were specific suggestions for specialised coworking spaces build to connect and learn rather than generate profit, but also a broad call for a long-term vision for the economic system that would redefine the purpose of work and its relation to status, power and wealth. This could in turn result in working less, reduced material consumption, and the possibility of slowing down and doing deep focused work. Participants agreed that we need a more solidary labour market that puts humans first and offers equal security whether working on a traditional contract or not. Finally, the participants called on companies to offer more transparency, communication and inclusion and to work with triple bottom lines considering both financial, social and environmental costs and gains.

Rights of the Future

Attempting to make the above ideas more concrete, participants suggested, among other things, that “everybody should have the right to internationally recognised digital nomadic contracts ensuring benefits such as education perks and paid parental leave for freelancers” and that “everybody should have the right to autonomously participating in determining one's own work conditions, culture and purpose of the company one work for”. The call for the right to universal basic income was mentioned too, as a solution to many of the considerations raised in the workshop.

Impact, Connection and Community

The workshop offered a much-needed forum in which to discuss and exchange experiences among the participants. The conversations in themselves offered an outlet, emphasising the need for community in an increasingly disconnected and tech driven labour market.

Another central takeaway was the strong call for direct impact through ones working life and active influence on ones working life. The option to choose between more alternatives than just full time or part time, the possibility of working at a place and time – and for a purpose – of one's own choosing.

What’s next?

In IDA we bring these insights home to help us in our continued work for our members and as input in the ongoing discussions about the role of trade unions in the near and far future.

Since the future of our work life might change due to digitalization and development of new technologies, and since our members have the necessary skills to build the infrastructure of a future labour market, IDA think it is important to host conversations around the topic and to listen to concerns and reflections from the people who will be affected by it, and so the journey does not end here.

What would you like the future of work to look like, and what are you going to do to make it happen?

What would you like to see IDA do?