Has your union representative made a difference for you and your colleagues? Then you can say thank you by nominating them for the Union Representative of the Year award.

News

Freedom with responsibility: When employees choose their own tasks

Employees at Pingala’s offices in Brøndby

“You get treated like an adult individual”.

Lise Holck’s description of what makes the IT consultancy Pingala a special place to work seems almost too simple to believe.

But this experience is a first for the IT consultant when she compares her current position to previous ones. Previously she felt reduced to a resource rather than a person – and felt that she had to follow a fixed development model in her work, “whether it made sense to or not”.

In Pingala she is free to choose how to approach a task. In fact, she chooses which tasks to work on.

“I am in charge of my own schedule and what I’d like to do. No one comes and tells me what to do. In return, I am responsible for keeping updated and taking on projects”, she explains.

About Pingala

Pingala is an IT consulting firm that advises businesses in process optimisation and implements ERP/CRM/BI solutions with Microsoft Dynamics 365 Finance/AX as focus point.

It is a criterion that all employees have at least 10 years of industry experience working with these Microsoft solutions.

It may sound utopic to give free reign to employees, but since 2013, Pingala has grown from 5 to 70 employees and has won the Børsen Gazelle award 7 years in a row.

In the process, the company has focused on building a culture where everyone feels an obligation to their co-workers and work tasks, so that there is no need for control or a tight organisational structure. That is why you will find no middle-level managers or salespersons, while other functions such as administration, HR and marketing are typically outsourced as needed.

That creates an organisation with a simple structure consisting of an administrative director at the top and 69 consultants and developers, all at the same level, below.

And it is not just the tasks that employees get to choose. They also choose when and where they will work. As a starting point they are contracted to 37.5 hours per week, but internal hours are not registered, and you do not have to ask for permission to take a Monday or Tuesday off every now and then.

“If my schedule shows I don’t have any pressing tasks, or that these can wait until tomorrow, I’ll just take a day off and spend it on private matters”, Lise Holck says.

To Kent Højlund, who is CEO, the idea is that employees know best what works for them.

“Your contract may say 37,5 hours per week but walks of life differ a lot. If you just had triplets, perhaps you are able to work for 30 hours a week during off-peak hours, while others would prefer to slave away for 2 months and then take a month off to travel”, he explains.

A simpler system works because employees are paid a basic salary, and on top of that receive a bonus every time they invoice an hour. It is up to them to find the right balance between salary and hours.

Most do go for a pretty average 9-17 workday, although Kent Højlund cannot say for sure how many do so:

“I have no idea since I don’t check their timetables”.

He only comments on employees’ working hours in situations where he can see that they invoice for many hours during a longer period.

“We won’t risk that anyone suffers a burnout from working here. We have previously approached employees at the brink of it, but luckily, we have had no sick leaves caused by stress”.

An oasis for the few

Although Pingala have a goal of being an oasis for employees and a place with room for diversity, admissions are strict. According to Kent Højlund, the company only recruits from the top ten per cent within their field, and all new hires must have at least then years of experience working as consultants.

Ever since the beginning of Pingala, hiring only the best talent and giving them absolute freedom has been a deep-rooted part of the strategy, Kent Højlund says. He explains that Pingala does not want to compete with major companies in terms of salary, but that they are able to offer some radically different terms of employment.

“When I have interviewed candidates, I notice some patterns. Many candidates have experienced really bad middle-managers, and if they can avoid that, they are happy. They are also interested in joining us because they would like to be free to organise their own workdays. They are tired of meaningless meetings and micromanagement from their superiors”, he explains.

CEO of Pingala, Kent Højlund.

The strict requirements for potential candidates set a natural limitation on the degree of diversity among employee profiles in Pingala. But Kent Højlund believes that his employees are very different at a personal level.

“I have a co-worker who always tells me; It is incredible how you always manage to hire another person entirely different from the others. But then my wife always says that we are all quite similar because we are a bunch of nerds”, he laughs.

Lise Holck also thinks that Pingala is characterised by giving everyone room to be themselves entirely – or “a bit weird”, as she puts it.

“there is a great deal of tolerance of each other’s differences, and it is self-evident that if I want a great deal of freedom in my work, then I must allow the same for others”.

Kent Højlund adds that the simple structure takes away internal competition and leads to a better working environment.

“We have no middle-managers so there is no competitions for promotions. You can be the lead on a project, and people take turns to be that, but after a while people are also happy to step back a little and give room to others, so they themselves can take a little break”.

Co-workers are bound closely together

“Our DNA, culture and values – that’s our product” Pingala write on their website.

It may sound like hot air, branding or a declaration of intentions following one of those internal workshops all employees are occasionally made to attend. But according to Kent Højlund, Pingala’s employees have adopted the idea because everything there happens on a voluntary basis. Small teams – or employee circles – are responsible for making on-going suggestions for developing the methods or culture of the company.

Employees come up with the tasks of the circles, and if no one volunteers to join a circle, it is simply skipped.

“It probably wasn’t that important anyways then”, Ken Højlund says.

One of the things Pingala has introduced following the suggestion of such an employee circle is that annual performance reviews have been replaced by mentor sessions between co-workers. Each employee has two mentors who provide feedback and are available to discuss professional challenges.

“These mentor groups have complete freedom in deciding how to apply their resources, or if they want to prioritise spending their time on supplementary training instead. This approach is widely different from other workplaces where the annual performance reviews sometimes feel like mere pro forma, and where the development of employees is welcomed, as long as it does not cost time or money”, Kent Højlund says.

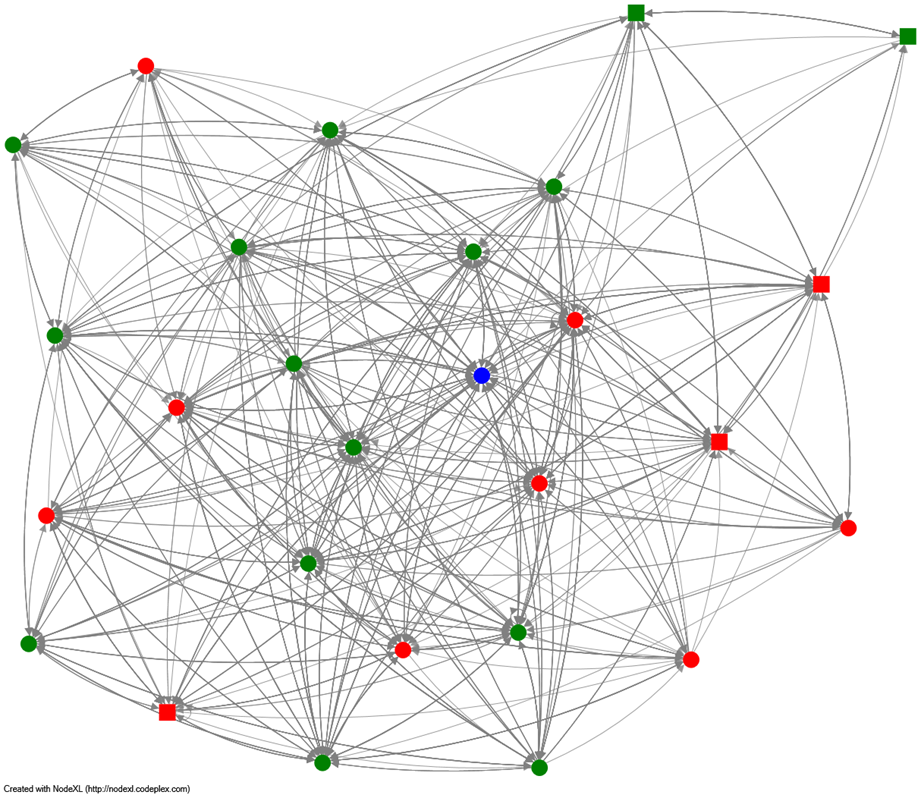

That employees are instead asked to use each other becomes evident in an annual network analysis. Kent Højlund shows an illustration where small dots are connected in an elaborate web. The green dots represent consultants, the red developers and the blue dot is Kent himself. The connections between the dots represent which employees often communicate with each other.

Illustration of Pingala’s organisational networks in 2018

Kent Højlund shows an illustration of the organisational networks from a previous year. In the model, three green dots make out a little island separate from the rest. The dots represent a small BI-firm of three people, who had joined Pingala at the time. But the collaboration with the rest of Pingala was never close, because the three new co-workers continued working as a separate unity without integrating in the rest of the company. Although, from a financial perspective, keeping the three made sense, their collaboration with Pingala ended because it did not contribute to developing the community of the company.

That community has, according to Kent Højlund, been highlighted during the corona lockdown. He was approached by several employees who suggested accepting salary cuts to avoid being fired – a scenario which was never close to becoming a reality. But the sense of community is also expressed under less dramatic circumstances: He has never experienced that employees rejected a task, although they are free to do so.

“They know that if no one volunteers, I have to contact the customer and say “I’m sorry, but we cannot solve that task”. And I think that’s why they volunteer, because they care about what is beneficial to their place of work. This is our oasis, and if we are to secure it, the company’s economy is part of that.”

To Lise Holck the issue is even more concrete.

“It isn’t just about the workplace, but about the people. For me this is not just an institution, it is almost a living organism”.